The Voynich Manuscript is a mysterious illustrated codex from the early 15th century, written entirely in an unknown script that no one has ever been able to read.

Often called the world’s most mysterious manuscript, it has baffled cryptographers, linguists, historians, and amateur codebreakers for over a century. The roughly 240-page book contains vivid illustrations of unidentifiable plants, astronomical diagrams, zodiac symbols, bathing women, and what appear to be pharmaceutical recipes, all accompanied by flowing text in a script known as “Voynichese.”

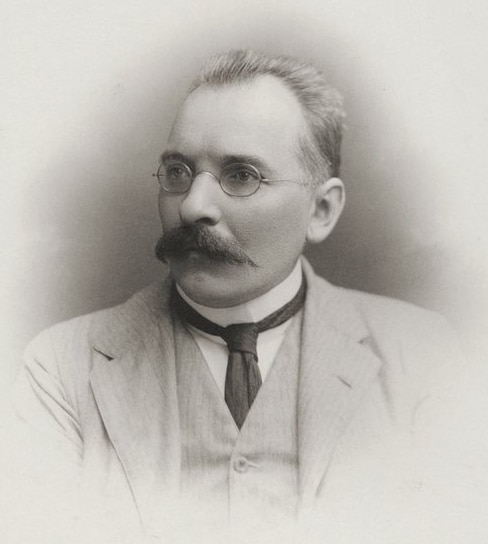

The manuscript is named after Wilfrid Voynich, a Polish-born rare book dealer who purchased it in 1912 from a Jesuit library near Rome. It has been housed at Yale University’s Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library since 1969, where its digitized pages remain among the most-viewed items in the collection.

Quick Facts

Created: Between 1404 and 1438 (radiocarbon dated)

Origin: Likely northern Italy (based on stylistic analysis)

Script: Unknown, referred to as “Voynichese”

Pages: Approximately 240 (originally estimated at 272)

Dimensions: 23.5 x 16.2 cm (9.3 x 6.4 inches)

Current Location: Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University

Catalog Number: MS 408

Named After: Wilfrid M. Voynich (1865-1930)

Discovery and Provenance

The modern story of the Voynich Manuscript begins in 1912, when Wilfrid Voynich purchased it as part of a collection from the Jesuit College at Villa Mondragone near Frascati, Italy. Tucked inside the manuscript was a letter dated 1665 or 1666, written by Johannes Marcus Marci, a physician and rector of Charles University in Prague. In the letter, Marci sent the book to the Jesuit scholar Athanasius Kircher in Rome, noting that it had reportedly been purchased by Holy Roman Emperor Rudolf II for the enormous sum of 600 gold ducats.

Recent archival research by Stefan Guzy of the University of the Arts Bremen has shed new light on how the manuscript may have reached Rudolf II. Guzy’s examination of imperial account journals uncovered records suggesting that physician and alchemist Carl Widemann sold a collection of manuscripts to Rudolf in 1599 for 500 silver thaler, an amount recorded elsewhere as its equivalent in gold: 600 florin. Widemann had lived in the house of Leonhard Rauwolf, a noted Bavarian botanist, and may have inherited books from Rauwolf’s estate after his death. A manuscript filled with unusual plant illustrations would have been an obvious item of interest for a botanist’s collection.

Before Rudolf II, the manuscript’s ownership trail goes cold for roughly 150 years. After Rudolf’s court, it passed to his court pharmacist Jacobus Horcicky de Tepenecz, whose signature has been detected on the first page under ultraviolet light. It later came into the possession of Georg Baresch, a Prague alchemist who is the first confirmed owner. Baresch struggled with the text and sent sample copies to Kircher in 1639, describing the book as a riddle that had been taking up space in his library. Upon Baresch’s death, the manuscript passed to his friend Marci, who forwarded it to Kircher. After Kircher’s death in 1680, the manuscript remained in Jesuit libraries for over two centuries until Voynich found it.

Voynich spent the rest of his life trying to decipher and promote the manuscript. He toured the United States in 1921, declaring it would “startle the scientific world.” He died in 1930 without ever cracking its code. His widow, Ethel Voynich, kept it in a bank vault for decades. After her death in 1960, the manuscript was sold by Voynich’s former secretary to rare book dealer H.P. Kraus, who donated it to the Beinecke Library in 1969.

Physical Description and Contents

The manuscript measures about the size of a modern paperback and is written on vellum (calfskin parchment). Radiocarbon dating performed at the University of Arizona in 2009 placed the creation of the vellum between 1404 and 1438. The ink has also been dated to the 15th century, making it extremely unlikely that the manuscript is a modern forgery on old parchment.

The text is written in a unique alphabet of roughly 20 to 25 distinct characters, though estimates vary depending on how symbols are separated. The writing flows smoothly with almost no visible corrections, suggesting the scribes were well-practiced with the script. Modern handwriting analysis has identified at least five different hands in the manuscript.

Nearly every page features colorful illustrations in greens, browns, yellows, blues, and reds. Scholars generally divide the manuscript into six sections based on these illustrations.

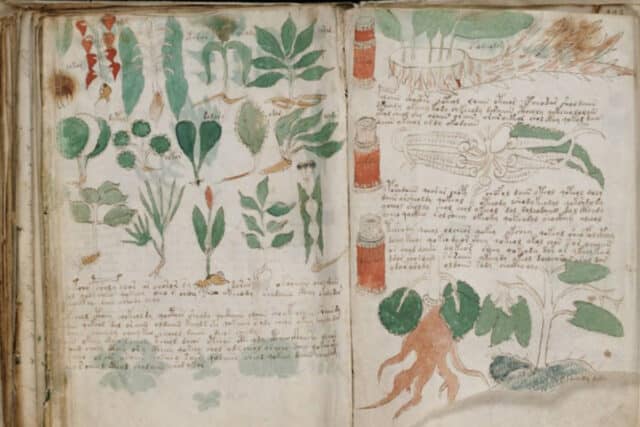

Herbal/Botanical Section: The largest portion of the manuscript, featuring detailed drawings of over 100 plants. Most of these plants do not correspond to any known species, though some bear resemblances to real herbs. A few pages feature bizarre details, such as balloon-shaped human heads growing from plants and a tiny green dragon sitting beside a plant’s leaves.

Astronomical/Astrological Section: Contains intricate diagrams of suns, moons, and stars, though none of the constellations are recognizable by modern astronomy.

Zodiac Section: Features zodiac symbols that closely resemble other 15th-century texts, though the order of signs sometimes differs from convention. Naked figures, both male and female, appear alongside the zodiac circles.

Biological/Balneological Section: One of the strangest portions. The illustrations depict nude women bathing in pools of green and blue water, connected by elaborate tubes and pipes. Some researchers interpret these as representations of medicinal bathing practices, while others see them as diagrams of human organs or the reproductive system.

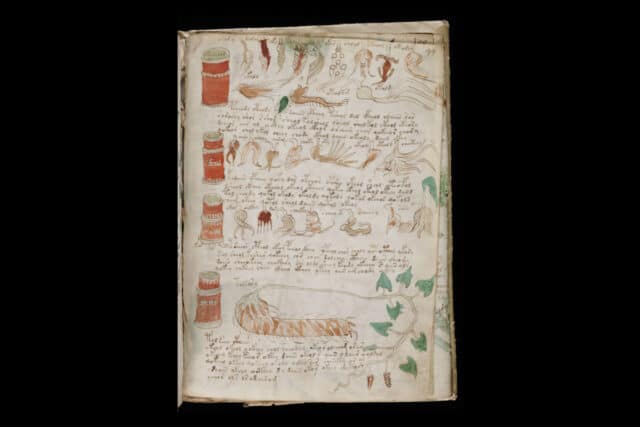

Pharmaceutical Section: Displays rows of ornate jars and bottles in red and blue, accompanied by drawings of plants and roots believed to represent medicinal ingredients.

Recipes/Star Section: A series of roughly 300 short paragraphs, each marked with a star-shaped symbol. Without the ability to read the text, the actual purpose of this section remains a guess.

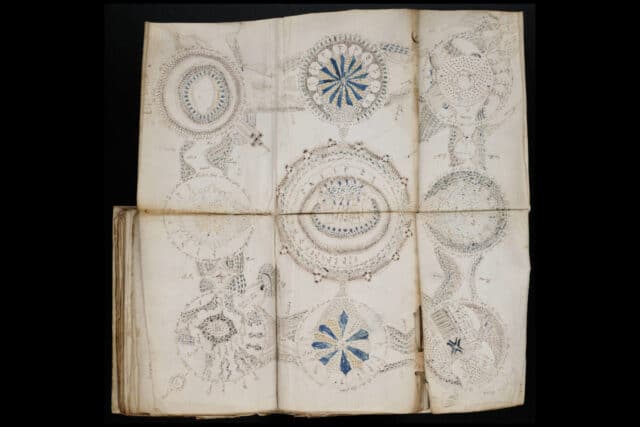

One of the manuscript’s most striking features is a large foldout section consisting of nine connected circles that include ramparts, towers, bridges, and turrets, giving it the appearance of a map.

Decipherment Attempts

The Voynich Manuscript has attracted some of the most skilled codebreakers in history, and not one of them has cracked it.

During World War II, renowned American cryptologists William and Elizebeth Friedman spent years studying the manuscript. William Friedman, who had broken complex military codes, ultimately concluded that the text might represent a constructed or artificial language rather than a cipher. British codebreakers, including members of the team that worked at Bletchley Park, also attempted to decode the text without success.

In the 1970s, military cryptographer Prescott Currier identified two statistically different text types within the manuscript, which he labeled “A” and “B.” This suggested either two different scribes, two different time periods of composition, or even two different underlying languages. His discovery opened new avenues of research that continue to this day.

The digital age brought computational tools to bear on the problem. In 2013, an information-theory study by physicist Marcelo Montemurro and colleagues found that the text displayed complex statistical patterns consistent with natural language rather than random gibberish. Word frequencies in the manuscript follow a Zipfian distribution, a hallmark of meaningful text. Linguistic analyses by Claire Bowern of Yale University found that while the script’s character-level predictability is unusually high compared to natural languages, its higher-level organizational patterns are consistent with either an encoded natural language or a well-constructed artificial one.

In 2019, University of Bristol researcher Gerard Cheshire claimed to have decoded the manuscript, identifying the text as a proto-Romance language. The university initially publicized the finding enthusiastically, but the claim was met with swift criticism from other scholars, and the university later retracted its press release. As one researcher noted, when you apply Cheshire’s substitutions and try to translate the result, the output remains incoherent.

A 2024 study published in Social History of Medicine proposed that the nine-rosette foldout diagram represents medieval understandings of the female reproductive system, with circles representing uterine chambers. The researchers suggested the manuscript may have been created by Bavarian physician Johannes Hartlieb as a coded treatise on sex and reproduction.

In 2025, a study proposed a historically plausible verbose substitution cipher called “Naibbe” that could encode Latin and Italian in a way that replicates many of the manuscript’s known statistical properties. However, the author stressed this was a proof of concept, not a definitive decipherment.

That same year, multispectral imaging revealed previously hidden columns of letters on the manuscript’s first page. Lisa Fagin Davis, executive director of the Medieval Academy of America, identified the handwriting as belonging to Johannes Marcus Marci, the 17th-century owner who had attempted his own decipherment over 350 years ago.

Despite all these efforts, no proposed decipherment has achieved consensus among scholars. As Yale’s Claire Bowern put it, the manuscript contains familiar topics presented in deeply unfamiliar ways, and working with it is difficult because any theory relies on many assumptions.

Major Theories

Theories about the Voynich Manuscript generally fall into a few broad categories.

Cipher or Code: The most traditional theory holds that the text is written in a cipher encoding a known language, most likely Latin or Italian. The smooth flow of the writing, the consistent use of the script across hundreds of pages, and the statistical patterns all support this possibility. However, no one has been able to produce a key that generates coherent translations.

Constructed Language: William Friedman’s theory that the text represents an artificial language created from scratch has gained support from some linguists. If true, it would predate other known constructed languages by centuries. The unusual statistical properties of the text, including its very low character-level entropy, fit this possibility.

Natural but Unknown Language: Some researchers have proposed that the text records a language or dialect that simply hasn’t been matched yet. Suggestions have ranged from Nahuatl (the Aztec language) to a Turkish dialect to a lost Romance language. None of these identifications have withstood scholarly scrutiny.

Elaborate Hoax: The possibility that the manuscript is meaningless gibberish designed to look like a coded text has been debated since its rediscovery. A recent experiment found that volunteers asked to write pages of fake text produced material with similar characteristics to the Voynich Manuscript, including patterns of word length variation and a process called “self-citation,” where new words are adapted from earlier ones. Science journalist Garry Shaw, who wrote a 2025 book about the manuscript, has said he leans toward the hoax theory, though he hopes he’s wrong.

Roger Bacon Attribution: An early and now-discredited theory attributed the manuscript to 13th-century English friar Roger Bacon. Voynich himself promoted this idea, but radiocarbon dating places the manuscript’s creation at least 150 years after Bacon’s death.

Cultural Impact

The Voynich Manuscript has become something of a cultural icon. It has inspired novels, television episodes, video games, music, and even manga. Its digitized pages on the Beinecke Library website are among the institution’s most popular items. Yale University Press published an official facsimile edition in 2016, and Garry Shaw’s 2025 book Cryptic: From Voynich to the Angel Diaries brought renewed public attention to the mystery.

The manuscript continues to attract fresh waves of amateur and professional researchers. New decipherment claims appear regularly, but as scholars note, the real test of any proposed solution is whether it can produce coherent translations of the full text, a bar that no one has yet cleared.

Where to View

The full text of the Voynich Manuscript is freely viewable online through Yale University’s Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library digital collection. The physical manuscript remains at the Beinecke Library in New Haven, Connecticut.

Whether the Voynich Manuscript holds genuine lost knowledge, a secret medical treatise, or the most elaborate medieval prank ever created, one thing is certain: its ability to captivate remains undiminished after six centuries. The answer, if there is one, still waits somewhere within those strange, beautiful pages.