What Are Out-of-Place Artifacts?

Picture stumbling across a pocket watch in a cave sealed for millennia or a microchip embedded in ancient stone. Out-of-place artifacts, often called OOPArts, are objects that seem to belong to a different time, discovered in places or eras where they shouldn’t exist according to mainstream history.

These enigmatic finds challenge our understanding of human development, suggesting possibilities like advanced ancient civilizations, time travel, or even extraterrestrial influence.

As someone who has always questioned the established narrative of human history, these mysteries push us to question the boundaries of what’s possible, blending wonder with a quest for truth.

OOPArts captivate us by hinting at hidden chapters in our past. They’re not just objects; they’re puzzles that spark debates between archaeologists, historians, and enthusiasts.

Some see them as evidence of lost technologies, while others suspect simpler explanations, like misidentification or natural processes.

This page explores 21 of the most famous OOPArts, diving into their discoveries, the extraordinary claims surrounding them, and the scientific realities that often ground these tales. Let’s unravel these mysteries together, keeping an open mind but a sharp eye for evidence.

Why Do OOPArts Capture Our Imagination?

OOPArts are more than curiosities—they’re gateways to the unknown. Their stories, often splashed across books, TV shows, and websites, tap into our love for the unexplained, fueling theories about ancient astronauts or forgotten empires. The idea that our ancestors might have wielded advanced tools or that visitors from another time left traces behind is thrilling. It’s no wonder these artifacts become legends, shared by those who crave answers to life’s biggest questions.

Yet, the allure of OOPArts being proof of lost ancient history, needs to be tempered against rationality.

Many turn out to be hoaxes, misinterpretations, or natural formations, revealed through careful analysis.

Still, their ability to spark curiosity endures, encouraging us to explore history with fresh eyes and ask questions that mainstream archaeologists won’t.

Whether they’re genuine anomalies or clever fakes, OOPArts remind us how much we still have to learn about our world. Below, we’ll examine each artifact, its origins, the claims that made it famous, and the facts that tell the real story.

Never Miss A Paranormal Story!

Newsletter subscribers get insider access to the latest paranormal posts!

Your email is safe with us and you can unsubscribe at any time!

1. Coso Artifact

Claims: Creationists, led by figures like Carl Baugh, claimed the hammer was millions of years old, as the surrounding rock was dated to the Cretaceous period (65–145 million years ago). They argued it proved humans coexisted with dinosaurs, challenging evolutionary timelines. The hammer’s encasement in hard rock suggested it was ancient, and some speculated it belonged to a prehistoric civilization with advanced metallurgy. The partially petrified handle added to the mystery, as petrification is thought to take thousands of years.

Reality: Geologists clarified that the rock is a concretion, not Cretaceous limestone. Concretions form when minerals precipitate around objects, sometimes in decades, as seen in studies by the USGS. The hammer is a 19th-century miner’s tool, likely dropped and encased near a quarry. Its iron head and wooden handle match designs from the 1800s, and partial petrification can occur in mineral-rich environments within years, as documented in Texas geology. Radiocarbon dating of the handle, conducted in the 1980s, confirmed a recent origin. The London Hammer is a classic case of geological misinterpretation fueling extraordinary claims.

2. Baghdad Battery

Claims: König proposed the jar was an ancient electric battery, capable of producing a small voltage for electroplating gold onto objects or for religious rituals involving mild shocks. This idea suggested the Parthians, or perhaps earlier Mesopotamians, had rudimentary electrical knowledge centuries before modern batteries. Enthusiasts pointed to the jar’s components—copper, iron, and an acidic electrolyte like vinegar—as evidence of sophisticated technology. The theory gained traction in popular media, with some claiming it proved ancient civilizations were far more advanced than historians believed.

Reality: Archaeologists and scientists lean toward a simpler explanation: the jar was likely a storage vessel for scrolls or other items. Similar jars from Seleucia, studied by the Penn Museum, share the same design but lack evidence of electrical use. Experiments, like those by the BBC in 2003, showed the jar could produce a weak current (about 0.5 volts), but no electroplated artifacts from the period have been found, undermining the battery hypothesis. The copper cylinder and iron rod are consistent with scroll holders, and the asphalt seal protected contents, not an electrolyte. The absence of wiring or related artifacts further suggests it was a practical, not technological, object, fitting Parthian material culture.

3. Aiud Object

Claims: The Aiud Object sparked theories of ancient or extraterrestrial technology. Its aluminum composition led some to argue it was a relic from a lost civilization or an alien craft, as aluminum requires complex processing unknown before 1825. Others suggested it was a tool or machine part from a time-traveling visitor, given its proximity to prehistoric bones. The object’s shape, with holes and grooves, fueled claims it was a component of advanced machinery, far beyond the capabilities of ancient humans.

Reality: Metallurgical analysis points to a modern origin. The object is likely a fragment of industrial machinery, such as an excavator tooth or aircraft part, lost during 20th-century construction or flooding. Aluminum’s industrial history rules out an ancient source, and its composition matches alloys used in modern equipment. The mastodon bones suggest a coincidental burial, as riverbeds often mix artifacts from different eras. No evidence supports extraterrestrial or ancient origins, and the object’s design aligns with mid-20th-century technology, as confirmed by Romanian archaeologists in the 1990s. This case shows how context can mislead initial interpretations.

4. London Hammer

Claims: Creationists, led by figures like Carl Baugh, claimed the hammer was millions of years old, as the surrounding rock was dated to the Cretaceous period (65–145 million years ago). They argued it proved humans coexisted with dinosaurs, challenging evolutionary timelines. The hammer’s encasement in hard rock suggested it was ancient, and some speculated it belonged to a prehistoric civilization with advanced metallurgy. The partially petrified handle added to the mystery, as petrification is thought to take thousands of years.

Reality: Geologists clarified that the rock is a concretion, not Cretaceous limestone. Concretions form when minerals precipitate around objects, sometimes in decades, as seen in studies by the USGS. The hammer is a 19th-century miner’s tool, likely dropped and encased near a quarry. Its iron head and wooden handle match designs from the 1800s, and partial petrification can occur in mineral-rich environments within years, as documented in Texas geology. Radiocarbon dating of the handle, conducted in the 1980s, confirmed a recent origin. The London Hammer is a classic case of geological misinterpretation fueling extraordinary claims.

Photo Credit: By Glen J. Kuban

5. Antikythera Mechanism

Claims: Early researchers called it an ancient computer, too advanced for Hellenistic Greece. Some speculated it was a gift from a lost civilization or extraterrestrial visitors, as its gears suggested knowledge of mechanics not rediscovered until the Middle Ages. The mechanism’s ability to predict astronomical events, like eclipses, led to claims of anachronistic technology, with popular media suggesting it could rewrite the history of science. Its precision and craftsmanship fueled theories of a forgotten technological golden age.

Reality: The Antikythera Mechanism is a genuine Greek artifact, used to calculate astronomical positions and cycles. Studies, including a 2006 Nature paper by the Antikythera Mechanism Research Project, show it aligns with Greek mathematical models, like those of Hipparchus. Its 30+ gears tracked the moon, sun, and planets, reflecting advanced but not impossible knowledge for the period. Cicero’s writings mention similar devices, and Greek engineering, seen in automata, supports its context. While extraordinary, it fits the Hellenistic era’s scientific culture, not requiring supernatural or alien explanations.

6. Maine Penny

Claims: The coin suggested Norse explorers reached Maine, far beyond their known settlements in Newfoundland. Some enthusiasts argued it proved Vikings established colonies deep in North America, predating Columbus by centuries. The penny’s pristine condition and context among Native artifacts led to theories of direct Viking-Native contact, with some claiming it hinted at a broader Norse presence in the New World. The find fueled romanticized tales of Viking adventurers charting unknown lands.

Reality: Archaeologists, including Bruce Bourque, propose the coin reached Maine through indigenous trade networks, not direct Viking exploration. Norse settlements, like L’Anse aux Meadows in Newfoundland (circa 1000 CE), traded with local tribes, and artifacts like the penny could travel hundreds of miles via exchange. Similar Norse items, like iron nails, have been found in Arctic trade routes. The coin’s context at a trade-heavy site supports this, and no other Viking artifacts (e.g., tools or runes) have appeared in Maine. The penny is a fascinating but indirect trace of Norse influence, not proof of a Maine colony.

7. Dropa Stones

Claims: The Dropa Stones were touted as extraterrestrial records, documenting an alien crash 12,000 years ago. The markings were said to tell of “Dropa” beings who taught locals advanced knowledge before dying out. Proponents claimed the discs’ grooves resembled phonograph records, suggesting ancient technology to store information. The story gained a cult following, with some linking it to China’s ancient astronomical traditions or myths of sky gods, portraying the discs as proof of alien contact.

Reality: The Dropa Stones are widely considered a hoax. No physical discs, skeletons, or caves have been documented by credible institutions, and the story traces to a fictional 1960 article by Sung Tze. Chinese archaeologists, including those at Peking University, found no record of Chi Pu Tei or the expedition. Similar “discs” in the region are natural jade objects, not alien artifacts. The tale’s spread through pseudoarchaeology books, lacking primary evidence, marks it as a fabricated narrative, exploiting fascination with ancient mysteries.

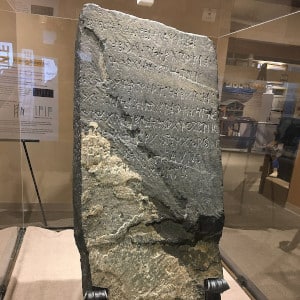

8. Kensington Runestone

Claims: The runestone was heralded as proof that Norse explorers reached the American Midwest 130 years before Columbus. Supporters argued it recorded a doomed expedition of 30 men, possibly Templar knights, venturing inland from Vinland. The inscriptions’ mention of a massacre and precise dates fueled romantic tales of Viking pioneers. Some claimed it validated Scandinavian heritage in America, challenging mainstream history and inspiring local pride in Minnesota’s Nordic communities.

Reality: Linguistic and historical evidence points to a 19th-century hoax. Runologist Henrik Williams and others note the runes use modern Swedish grammar, inconsistent with 14th-century Norse. Geological analysis, conducted in the 1980s, shows the stone’s weathering matches decades, not centuries, of exposure. Ohman, facing economic hardship, likely carved it to boost land value or cultural pride, as similar hoaxes were common among immigrants. No corroborating Norse artifacts exist in the region, and medieval Norse records lack mention of Midwest exploration, confirming the stone’s inauthenticity.

9. Nampa Figurine

Claims: The figurine was initially seen as evidence of human presence in North America millions of years ago, challenging evolutionary timelines. Creationists and amateur archaeologists argued it proved ancient humans had artistic skills during the Pliocene epoch, alongside early hominids. Its detailed features, like arms and legs, suggested a level of craftsmanship unexpected for such an ancient context, leading some to speculate about a lost civilization or divine intervention.

Reality: The figurine is likely a 19th-century Native American doll or a deliberate prank. Later studies, including those by the Idaho Geological Survey, found the well’s stratigraphy was misdated; the layer was closer to a few thousand years old, possibly from a recent intrusion. Similar clay figures are known from regional tribes, used in rituals or as toys. The lack of additional artifacts or cultural context at the site, combined with the era’s penchant for archaeological hoaxes, suggests it was planted or misinterpreted, not evidence of prehistoric art.

10. Malachite Man

Claims: Creationists argued the skeletons proved humans lived alongside dinosaurs, supporting a young Earth timeline. The Cretaceous dating, based on the surrounding rock, suggested the remains were millions of years old, contradicting human evolution models. Proponents claimed the skeletons’ intact state and human-like features ruled out natural deposition, pointing to a catastrophic flood or ancient human presence. The find became a staple in creationist literature, cited as evidence against mainstream geology.

Reality: The skeletons are post-Columbian Native American burials, misdated due to erroneous geological assumptions. Radiocarbon dating, conducted in the 1980s by the University of Utah, confirmed the remains are less than 500 years old, likely from a known indigenous cemetery disturbed by mining. The sandstone layer was a recent overburden, not Cretaceous bedrock, as clarified by USGS geologists. The malachite staining resulted from copper-rich groundwater, a common phenomenon. This case underscores how misreading stratigraphy can lead to dramatic but unfounded claims.

11. Wolfsegg Iron

Claims: Early reports suggested it was an ancient artifact or meteorite, given its polished appearance and ancient context. Pseudoarchaeologists later claimed it was a product of a prehistoric civilization or extraterrestrial visitors, as ironworking was unknown in the Tertiary period. Its geometric shape and groove led to theories of it being a tool or component of advanced machinery, fueling speculation about lost technologies preserved in coal seams.

Reality: The object is likely a piece of mining equipment, such as a counterweight or tool fragment, dropped during 19th-century operations. Metallurgical analysis, conducted in the 1960s by the Vienna museum, found it was cast iron, consistent with industrial-era production. Coal seams often trap recent objects during extraction, as documented in mining studies. The lack of prehistoric iron artifacts elsewhere and the object’s similarity to known mining tools confirm its modern origin, debunking claims of ancient or alien manufacture.

12. Dorchester Pot

Claims: The pot was hailed as evidence of ancient metallurgy, suggesting a civilization existed millions of years ago. Some speculated it was a relic of a lost race, possibly Atlantean, with advanced metalworking skills. Creationists cited it to challenge deep-time geology, arguing the rock’s age proved human artifacts predated modern timelines. The vessel’s intricate design and encasement in solid rock fueled theories of a forgotten technological era.

Reality: The pot is a Victorian-era candlestick or pipe holder, likely from a local household, encased in a natural concretion. Geologists, including those at MIT in the 1970s, noted that concretions can form around objects in years, not millions, as seen in coastal Massachusetts. The rock was misidentified as Precambrian; it was a recent deposit. Similar artifacts, identified in 19th-century catalogs, match the pot’s description, and no other ancient metal vessels have been found in the region. The story likely grew from quarry workers’ exaggeration or a publicity stunt.

13. Kingoodie Artifact

Discovery: In 1844, quarrymen at Kingoodie, Scotland, found a corroded, nail-like object embedded in a block of Devonian sandstone, dated to 360–400 million years old. Reported by Sir David Brewster in the British Association for the Advancement of Science, the 6-inch-long object was partially encased, with its head protruding. Little documentation followed, and no photographs or physical evidence survive, leaving the find shrouded in uncertainty.

Claims: Brewster suggested it was an ancient tool, implying human craftsmanship existed in the Devonian period, long before mammals. Later enthusiasts claimed it was evidence of time travel or a prehistoric civilization, as iron nails were unknown in such ancient rock. The object’s reported integration into the sandstone fueled speculation that it was deliberately placed millions of years ago, challenging geological and historical records.

Reality: The artifact is likely a modern nail or spike, encased in a concretion mistaken for sandstone. Geologists note that concretions can form around iron objects in decades, as seen in Scottish quarries. The lack of photographs, samples, or corroborating finds weakens the claim, and Brewster’s brief report may have exaggerated the context. Similar cases, like the London Hammer, show how recent objects can appear ancient due to rapid mineralization. Without evidence, the Kingoodie Artifact remains a footnote, likely a misidentified 19th-century relic.

14. Lake Winnipesaukee Mystery Stone

Claims: The stone was thought to be an ancient relic, possibly from a lost civilization or pre-Columbian visitors, due to its unique carvings. Some linked it to Celtic or Norse explorers, citing the arrow symbols, while others suggested Native American origins with an unknown purpose. Its polished finish and precise etchings led to claims of advanced craftsmanship, potentially ceremonial or astronomical, sparking debates about an undiscovered New England culture.

Reality: The stone is likely a 19th-century artifact or hoax, possibly crafted by a local artisan or Native American. Archaeological studies, including those by the NHHS in the 1990s, found no evidence of ancient origins, and its symbols don’t match known pre-Columbian styles. Similar carved stones were sold as curios in the 1800s, often to tourists. The lack of additional finds or cultural context suggests it was a one-off creation, perhaps buried deliberately to intrigue finders, aligning with the era’s fascination with archaeological fakes.

15. Saqqara Bird

Claims: In the 1960s, researchers like Khalil Messiha claimed the bird was a scale model of an ancient glider, suggesting Egyptians had knowledge of aerodynamics. Its wing shape and tail design, tested in wind tunnels, showed lift potential, leading to theories of advanced engineering. Some speculated it was used to study flight or as a ceremonial object symbolizing aviation, implying a technological leap far ahead of the Ptolemaic period.

Reality: Egyptologists identify the Saqqara Bird as a ceremonial object or child’s toy, likely representing a falcon, sacred to Horus. Similar wooden models, found in other tombs, lack aerodynamic features and depict birds in ritual poses. Tests by aeronautics expert Martin Gregorie in 2002 showed it couldn’t sustain flight without modifications, like a stabilizer. The tail’s shape is stylistic, not functional, and no evidence of Egyptian aviation exists. The bird fits Ptolemaic funerary art, not a blueprint for flight, debunking claims of ancient aeronautics.

16. Klerksdorp Spheres

Claims: Proponents claimed the spheres were artificial, crafted by a prehistoric or extraterrestrial civilization 3 billion years ago, when Earth had only microbial life. Their near-perfect roundness and grooves suggested machining, and some argued they were aligned with cosmic patterns, like constellations. Creationists used them to challenge deep-time geology, claiming they proved a young Earth with advanced inhabitants, making the spheres a staple of fringe literature.

Reality: The spheres are natural concretions, formed by mineral precipitation in volcanic sediment. Geologist Paul Heinrich, in a 2008 study, explained their spherical shape results from chemical processes in pyrophyllite, common in Precambrian deposits. The grooves are natural fractures, not carvings, as confirmed by microscopic analysis. Similar concretions, like Moqui marbles, form worldwide. No evidence of artificial crafting exists, and their age reflects the rock, not the spheres, aligning with geological consensus and debunking claims of intelligent design.

17. Baigong Pipes

Claims: The pipes were touted as remnants of an ancient or alien technology, possibly a plumbing system for a lost city or extraterrestrial base. Their uniform shape and alignment with a “pyramid” (a natural hill) suggested advanced engineering, unknown to prehistoric humans. Some claimed radioactive properties or cosmic origins, linking them to China’s myths of sky gods. The story spread globally, amplified by shows like Ancient Aliens, portraying the pipes as evidence of a forgotten civilization.

Reality: Geological surveys, including a 2003 study by the Chinese Academy of Sciences, identified the pipes as fossilized tree roots or mineral veins, formed by iron-rich groundwater solidifying in sedimentary rock. The “pyramid” is a weathered hill, not man-made, and no artifacts or structures support a technological site. Similar formations, like pipe-like concretions, occur globally, as noted in USGS reports. The pipes’ age reflects the rock, not their formation, and claims of radioactivity were unfounded. This case illustrates how natural geology can mimic artificial structures, fueling speculative narratives.

18. Costa Rican Stone Spheres

Claims: The spheres’ near-perfect roundness led to theories of extraterrestrial or Atlantean origins, as such precision seemed beyond pre-Columbian tools. Some claimed they were navigational markers, astronomical models, or ritual objects tied to lost civilizations. Their size and arrangement fueled speculation about advanced engineering, with myths linking them to Plato’s Atlantis or alien visitors, popularized in books like Chariots of the Gods. The mystery of their purpose captivated global audiences.

Reality: The spheres were crafted by the Diquís culture using stone hammers and chisels, as shown in archaeological experiments by Hoopes in 2010. Granite boulders were shaped and polished over weeks, achieving roundness through manual labor, a technique seen in other pre-Columbian art. Ethnographic records suggest they marked social status or ceremonial spaces, not cosmic maps. Radiocarbon dating and site analysis confirm their 700–1500 CE context, and no evidence supports extraterrestrial or Atlantean links. The spheres are a testament to Diquís ingenuity, not anachronistic technology.

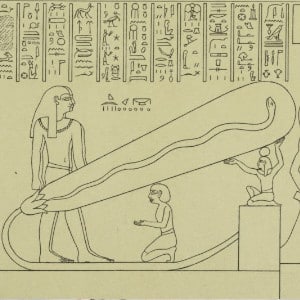

19. Dendera Light

Claims: Pseudoarchaeologists, starting in the 1990s, claimed the reliefs depicted electric lamps, suggesting ancient Egyptians had electricity for lighting temples. The “bulb” shape, “filament” (snake), and “cord” were interpreted as a working circuit, possibly powered by batteries like the Baghdad Battery. Proponents argued this explained how deep tombs were illuminated without soot, pointing to a lost technological era. The theory gained traction in fringe media, portraying Egyptians as electrical pioneers.

Reality: Egyptologists, including those at the University of Leiden, identify the reliefs as mythological symbols: a lotus flower (the “bulb”) birthing a snake, representing the god Harsomtus and creation myths. Similar motifs appear in other temples, like Edfu, with no technological context. No electrical artifacts, wiring, or soot-free lamps have been found, and tombs used mirrors or oil lamps, as evidenced by archaeological remains. The cord is a stylistic element, not a cable. The reliefs fit Ptolemaic religious art, not evidence of electricity, debunking claims through cultural and material analysis.

20. Iron Pillar of Delhi

Claims: The pillar’s rust resistance led to claims of advanced metallurgy, possibly from a lost civilization or extraterrestrial guidance. Some argued its iron purity and forging surpassed Gupta-era capabilities, suggesting knowledge of anti-corrosion techniques unknown until modern times. Pseudoarchaeologists linked it to ancient astronaut theories, claiming it was a beacon or relic of superior technology, given its durability in India’s humid climate.

Reality: The pillar is a genuine Gupta artifact, its rust resistance due to a passive oxide layer formed by high-phosphorus iron and unique forging, as shown in a 2003 IIT Kanpur study. The dry Delhi climate and occasional oil coatings by locals enhanced its preservation. Metallurgical analysis confirms the iron was smelted using known Gupta methods, like bloomery furnaces, producing low-carbon steel. Similar pillars exist from the period, though less preserved. The pillar’s craftsmanship is remarkable but consistent with Gupta metallurgy, not requiring supernatural or alien explanations.

21. Russian Toothed Wheel

Claims: The toothed wheel ignited speculation about advanced ancient technology or extraterrestrial origins. Its composition—98% pure aluminum with 2–4% magnesium—suggested high-tech manufacturing, as pure aluminum is rare in nature and requires sophisticated processing. Some, including ufologist Valery Brier, claimed it was a fragment of an alien spacecraft or a relic of a prehistoric civilization, arguing the coal’s age placed it before human history. Creationists and pseudoarchaeologists cited it as evidence of a young Earth or lost societies, with its gear-like shape hinting at machinery far beyond the Carboniferous era’s microbial life.

Reality: Despite the intrigue, the toothed wheel is likely a modern industrial fragment, possibly from mining equipment, encased in coal. Aluminum’s industrial origin post-1825 rules out ancient manufacture, and its purity matches 20th-century alloys, as confirmed by X-ray diffraction studies cited in Russian reports. The coal’s 300-million-year age reflects the seam, not the object, which could have been introduced during mining. Geologists note that soft aluminum is unlikely in coal mines due to sparking risks, but similar finds, like the Aiud Object, are often misidentified machinery parts. The lack of the original sample, rigorous documentation, or peer-reviewed studies, combined with Brier’s ufology background, suggests the story was exaggerated by sensationalist media, leaving the object’s true nature unresolved but terrestrial.